We’ve put together a list of all the 8-marker microeconomics questions from Edexcel A-Level Economics past papers. Our goal is to save you time trawling through all of the past papers to pick out which questions you want to answer. It is a good idea to focus on specific types of questions because 8-markers are graded differently from questions that give you more or fewer marks.

What is the Edexcel A-Level Economics test?

The Edexcel A-Level Economics test is a qualification designed to prepare high school students to study economics at university. Pearson Edexcel offers this particular instance of the Economics A-Level but you can also take the A-Level in Economics from AQA, OCR, CIE, WJEC, and Eduqas.

Edexcel is a privately-owned British education and exams body founded in 1996. Edexcel has been owned by Pearson plc. since 2005. Edexcel produces qualifications and tests for the British education system and is the UK’s largest entity offering educational qualifications.

Where did we get these Edexcel Economics A-Level Past Paper Microeconomics 8-marker Questions?

We went through all of the Edexcel A-Level Economics past papers available online and pulled out the microeconomics 8-marker questions. The resulting list is intended to help you practice answering 8-markers without having to go through all the past papers yourself. You’ll find the answer key at the end of this page in downloadable pdf form.

Want questions for other topics in A-Level Economics? You can find more A-Level Economics Past Paper Questions here.

What is Microeconomics?

Microeconomics is the study of how individual businesses and consumers make decisions about the allocation of resources. Microeconomics is concerned with why a specific individual would choose to purchase one product over another or how a business decides how much of its product to produce.

Microeconomics is often contrasted with macroeconomics, which is the study of economy-wide phenomena like inflation, unemployment, and monetary and fiscal policy. While macroeconomics might study how increasing interest rates affects inflation, microeconomics studies how a tax on cigarettes affects cigarette consumption.

You can check out our Edexcel A-Level Economics Notes here.

How to answer Edexcel Economics 8-markers?

Answer Edexcel Economics 8-markers by making two simple points that directly answer the question and fulfil the marking criteria of 2 knowledge, 2 analysis, 2 application, and 2 evaluation points.

An example of how to satisfy these criteria within each point would be to identify a factor that answers the question (1 knowledge point), pull one data point from the extract that aids your answer (1 application point), provide one linked analysis for why the factor influences an outcome (1 analysis point), and identify one counterargument for this factor (1 evaluation point).

You will encounter 8-marker questions on all three papers of your Edexcel A-Level Economics test and the questions should take you 8 minutes to complete.

How are Edexcel Economics 8-markers marked?

All Edexcel Economics 8-markers are marked based on whether you secure 2 knowledge points, 2 analysis points, 2 application points, and 2 evaluation points.

You can secure 2 knowledge points by either offering 2 relevant definitions or 2 factors that influence the answer to your question. For example, if a question asks you to examine the benefits of a tax on cigarettes, you could identify 2 potential benefits in order to get 2 knowledge points. Alternatively, you could provide a definition of an indirect tax.

You can secure 2 analysis points by offering 2 instances of chained analysis. As you are only looking for 2 points, these chains can be as simple as A → B. For example, if you wanted to argue that a benefit of a tax on cigarettes the elimination of the negative externality of the health risks associated with cigarette use, you could argue that the tax on cigarettes increases their price. This price increase would price some consumers out of the market and may deter others by shifting their cost-benefit analysis. As a result, fewer people consume cigarettes, which brings the equilibrium more in line with the socially optimum point.

You can secure 2 application points by pulling two data points from the extracts that support your argument. For example, data on the number of cigarette-related health risks would support the argument about indirect taxes eliminating this externality.

Finally, you can secure 2 evaluation points by identifying one counterargument for each of the two points you offer in your answer. This question is only an 8-marker so you do not need to go into depth with your explanation of these points. You only need to identify them. For example, you could argue that cigarettes are addictive and therefore price increases may not have a meaningful effect on their consumption (low price elasticity of demand).

Question 1: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 1

Extract B

Thomas Cook’s environmental impact

Thomas Cook Group plc’s operations included its airline and 560 high street travel agents providing flights, hotels and package holidays.

The environmental impact of the travel industry is significant. It accounts for 8% of all global carbon emissions. Thomas Cook recognised the risks presented by climate change and actively engaged in reducing their airline emissions. Its plans included using more efficient aircraft and using lower-carbon fuel. In 2018, Thomas Cook was included in the top 10 of the world’s most fuel-efficient airlines.

(b) Examine the likely impact of Thomas Cook’s plan ‘to reduce their airline emissions’ (Extract B, line 6) on the social optimum position. Use an appropriate externalities diagram in your answer. (8 points)

Question 2: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2020 Paper 1

(b) With reference to Figure 2, examine two possible factors which may have influenced the demand for rail travel since 2008. (8 points)

Question 3: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2019 Paper 1

Extract B

BT profit rises

BT Group, which includes BT Openreach and BT Retail, reported a rise in profit as revenue increased following the integration of the consumer mobile business, EE. BT finalised the takeover of EE in August 2016, and the integration has resulted in BT controlling 35% of the mobile consumer market. The profit of the UK-based telecommunication group in its second quarter 2017 rose to £566 million.

BT Group chief executive Gavin Patterson said: “We will operate a multi-brand strategy with UK customers being able to choose a mix of BT, EE or Plusnet services, depending on which suits them best. The acquisition enables us to offer great value bundles of services and customers are set to be the winners as we compete for their business”.

(b) With reference to Extract B, examine the likely benefits to consumers of the integration between BT and EE. (8 points)

Question 4: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2018 Paper 1

Extract A

Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) report into the UK energy market

An investigation into the UK energy market by the CMA concluded that customers have been paying £1.4 billion a year more than they would in a fully competitive market. It found that 70% of domestic customers of the six largest energy firms were on an expensive standard rate. These customers could each save over £300 a year by switching to a cheaper deal but appear reluctant to do so.

However, the CMA investigation found no evidence of anti-competitive practices by firms. There has even been an increase in new entrant energy suppliers over recent years and their combined market share has reached 12% in both gas and electricity supply. To protect consumers, the CMA has introduced various measures to open up and increase competition in the UK energy market. These include:

- the creation of a database designed to help consumers switch energy suppliers – rivalsuppliers can directly contact these customers

- the conversion of all homes to smart energy meters making it easier for customers to measure energy consumption and switch supplier

- new rules to protect the four million vulnerable customers using prepaid meters – this includes a temporary price cap until smart meters have been installed.

(d) With reference to Extract A and your own knowledge, examine two possible reasons for the change in price elasticity of demand for electricity over time. (8 points)

Question 5: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2017 Paper 1

Extract A

Supermarket price war puts pressure on their food suppliers

The number of food suppliers (to supermarkets) struggling to remain in business has increased by more than 50% over the past year as supermarkets engage in an intense price war. It has never been tougher for the UK’s food suppliers according to a study by accountants Begbies Traynor. It blames aggressive price-cutting by the supermarkets and delays in payments to food suppliers as the main causes of the difficulties. Further problems include food suppliers being forced to pay excessive amounts for packaging specified by supermarkets and funding in-store promotions. Almost 90% of struggling food suppliers are small and medium-sized businesses. The price war has contributed to food prices paid by consumers falling by 1.7% over the past two years.

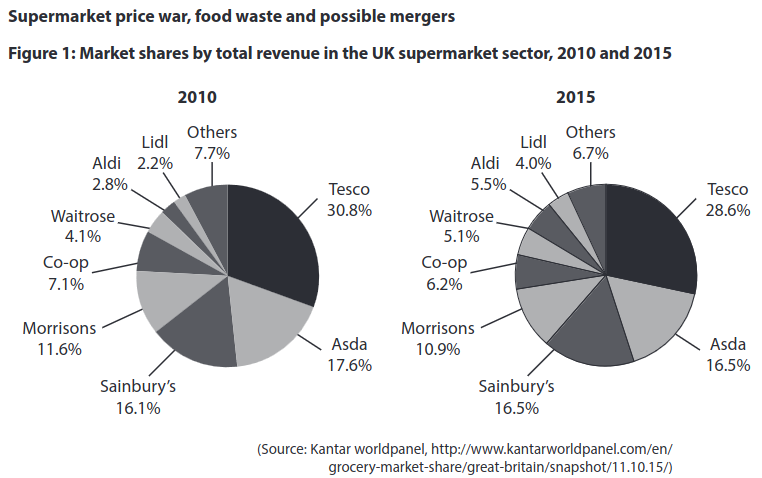

The market shares of the big four supermarkets – Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons – are under pressure as shopping habits change. Many consumers are switching from one main weekly shop to shopping more frequently at local discount stores such as Aldi and Lidl or purchasing goods online from other grocery retailers.

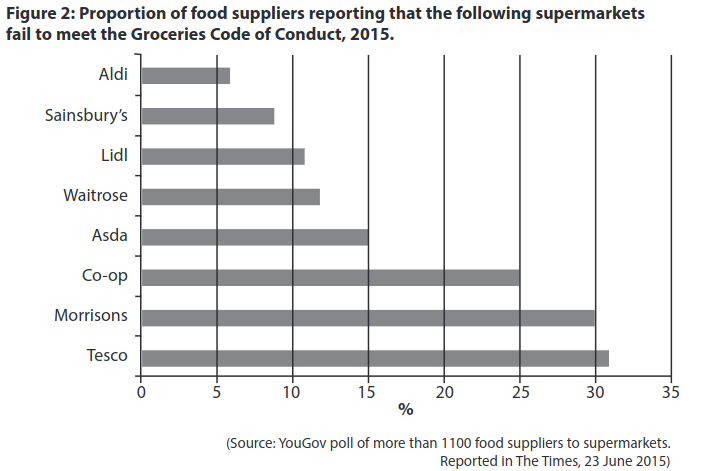

The big four supermarkets have responded by putting more pressure on their suppliers despite an investigation by the Groceries Code Adjudicator (GCA). The GCA has the power to fine supermarkets up to 1% of their annual sales revenue if they break the Groceries Code of Conduct. A YouGov study found considerable differences between the supermarkets in meeting the Code with Aldi performing well but Tesco badly. Despite the Groceries Code, many food suppliers are reluctant to complain for fear of losing contracts with the supermarkets.

Extract B

Food waste in the supply chain

A report from the British Retail Consortium reveals that supermarkets are directly responsible for around 0.2 million tonnes of food waste every year. This is due to the expiry of use-by-dates and poor handling of stock.

However, 4.1 million tonnes of food waste occurs annually in the food supply chain before it even reaches the supermarkets, indicating the existence of information gaps. The supermarkets are cooperating with food suppliers and farmers to try to reduce this waste. This involves improving forecasts for supply and demand of food and increasing the reliability of transportation and storage.

Consumers, the final stage of the supply chain, waste a further 7 million tonnes of food each year. This suggests irrational behaviour. Supermarkets are also working with consumers to reduce the waste by providing advice on how to store and use leftover food. The development of packaging designs to keep food fresher for longer is one of the innovations under way to reduce waste.

Extract C

Proposed merger activity in the supermarket sector

Analysts at Société Générale, an investment bank, have recommended a merger between

Sainsbury’s and Morrisons. They claim it would lead to increased economies of scale and market power for the combined business. Such a merger between the third and fourth largest supermarkets in Britain would have been unrealistic a few years ago due to concerns of its impact in reducing competition. However, the chances of getting permission from the Competition and Markets Authority have increased following the growth of Aldi and Lidl. Giant mergers have been approved in other sectors such as Lloyds-HBOS (banking) and British Telecom-EE (telecommunications).

The suggested merger would have its challenges. There is considerable overlap between the locations of the stores and the enlarged company would require the rationalisation and co-ordination of hundreds of thousands of employees. A new expensive IT system is likely to be required and the underlying difficult market trends would remain in the food retailing industry.

(c) Examine measures the government might use to restrict the monopsony power of supermarkets. (8 points)

Question 6: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 3

Extract A

What is the true human cost of your £5 hand car wash (HCW)?

The UK’s hand car washes (HCWs) are extremely price competitive, but they have also been linked to modern slavery. Are they ever fair for workers? There is little agreement about how many HCWs there are in the UK. Estimates range from 10 000 to 20 000. This lack of accurate information about the industry makes government regulation very difficult. Automated car washes, with their fierce rotating bristles, used to be the first option for drivers in a hurry. Now there is more choice.

While the economy slows and incomes fail to keep up with inflation, demand for HCWs has grown. Many people see paying £5 for a car washed by someone else, rather than cleaning it at home, as a small expense which yields a high utility. But what is the true cost of a £5 car wash – and what should we be paying?

The growth of HCWs is partly the result of changes in the structure of industry in the UK. Many petrol stations have closed as drivers fill up at supermarkets. Garages and their forecourts have closed as cars become more reliable and locked into service agreements. The available sites for HCWs have therefore increased significantly and rents have fallen. HCW entrepreneurs have identified available land and have benefitted from changes in the labour market, partly as a result of EU migration. UK drivers are now able to obtain cheap and effective hand car washing. For many migrants, car washes are a first job.

“They accept car washing for a short period while they improve their language skills and move into other industries,” says Ian Clark, a professor of work and employment at Nottingham Business School. “But there are also car-wash workers without networks who are in a dead end, working there for long periods.”

Many drivers are only interested in getting the cheapest wash. If the price is very low, it probably means that workers are receiving less than the minimum wage and working in poor conditions. Crude calculations illustrate the problem. A £5 HCW employing five workers for 10 hours a day would need to wash 79 cars a day to just cover the wage costs. This assumes the workers are paid the minimum wage. This is one car every seven and a half minutes. Even if the profit can be higher on valet services, the price of which can be as little as £12 for a full inside-and-out clean, it’s hard to see how a car wash price as low as £5 pays a living wage. This ignores all other costs which HCWs incur such as business rates and rent.

Evidence from car-wash workers is limited but Clark and others have been able to build a picture of some of the tougher conditions on drenched forecourts. “Like nail bars and small garment manufacturers, car washes are what we call ‘hard-to-reach places,’” Clark explains. As part of the research, Clark and his team spoke to workers from 45 HCWs in the Midlands.

Clark and his team met and observed workers who lacked waterproof boots or trousers, or hi-vis jackets and gloves. “They’re spraying around hydrochloric acid solution for alloy wheels, breathing in the vapour and fumes,” Clark says. Some workers were paid a little over half the minimum wage.

(b) Examine two reasons why the demand for HCWs increases during a period when consumer ‘incomes fail to keep up with inflation’ (Extract A line 8). (8 points)

Question 7: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 3

(b) Examine two likely effects of the forecast change in the rate of unemployment between 2019 to 2020, on firms in Germany. Refer to Figure 4 in your answer. (8 points)(b) Examine two likely effects of the forecast change in the rate of unemployment between 2019 to 2020, on firms in Germany. Refer to Figure 4 in your answer. (8 points)

Question 8: Edexcel A-Level Economics June 2019 Paper 3

Extract E

Mozambique’s economic stability is being put to the test

The economy of Mozambique, which gained independence from Portugal in 1975, has continued to under-perform. Large-scale emigration, especially of skilled workers, economic dependence on South Africa, a severe drought, a prolonged civil war and political tensions have hindered the country’s development. More than half of Mozambique’s 26 million people continue to live below the poverty line.

GDP growth declined to 3.6% in 2016 due to fiscal tightening and a slowdown in foreign direct investment. A weak manufacturing sector employs just 3.2% of the population, and is made up of small enterprises (90%), many of which were set up with the aid of microfinance. Traditional export earnings dropped due to depressed global demand.

In addition a wide-scale drought seriously affected agricultural production. Foreign currency inflows have weakened – as large-scale gas projects were put on hold, and 14 external lenders suspended direct budget support, as a lesson to be learned from the tuna-fleet scandal. The state budget deficit was 10.7% of GDP in 2017. High interest rates have reduced aggregate demand, and import costs added to inflation following further depreciation of Mozambique’s currency, the metical, to a new low of 100 meticals to £1. Mozambique needs urgently to improve its investment environment and confidence in its institutions. The World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness ranking placed Mozambique 136 out of 137 countries.

Longer term, Mozambique’s economic prospects are promising. There has been progress in talks on restoring international confidence in the government’s running of the economy, leading to a lasting and sustainable agreement between rival political groups. The development of gas fields off Mozambique’s coast discovered in 2011 is set to transform the economy, coming into production in the 2020s. A rise in coal and electricity exports should help growth to increase. But in the short term, it remains uncertain whether Mozambique can deliver badly needed economic stability.

(b) Examine two reasons, apart from access to finance, why 90% of the manufacturing sector in Mozambique ‘is made up of small enterprises’ (Extract E, line 9). (8 points)

Question 9: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2018 Paper 3

Extract B

Tax on disposable coffee cups?

Two and a half billion disposable cups are thrown away every year in the UK, that is, seven million every day. Only one in 400 is recycled. The UK Environment Minister has suggested that a coffee cup tax could work in a similar manner to the plastic bag charge. The 5 pence a bag charge has led to an 85% reduction in the number of bags being given out since October 2015. It is estimated that introducing a tax on disposable coffee cups would cut usage by two billion every year. One environment spokesperson, Kate Parminter, said: “We’ve seen how dramatically a small charge has affected public behaviour when it comes to the plastic bags and it is clearly time to extend it to coffee cups. Most people purchase a tea or coffee and throw away the cup without even thinking about it, but a charge would increase our awareness of the environmental impact.”

In response, another MP welcomed her comments but said he did not believe a tax was the solution. He said: “My initial reaction is charging 5p or 10p for the cup will not work. It will not encourage people to take their own cups in if a coffee goes up from £2.60 to £2.65. I suspect a more technological answer is what we need – either the composition of the disposable cups being changed so they’re more easily recyclable, or changing the technology in the recycling.”

Disposable coffee cups contain a plastic coating inside the cups which prevent them from becoming soggy, making them difficult to recycle. There are just two specialist facilities in the UK that have the required equipment to separate plastic from paper for recycling. Almost no recycled paper is used in the production of disposable cups, meaning that some 43 000 trees must be cut down annually to keep up with the demand. CO emissions of around 83 000 tonnes are generated every year for their production.

Extract C

German city of Freiburg takes action on cutting the use of disposable coffee cups

The ‘Freiburg cup’, made from dishwasher-proof plastic, can be reused hundreds of times. Cups are issued with a one-euro deposit, and can be returned to any of the participating coffee shops in the German city. The cups, which are provided to coffee shops by local councils, are washed in the cafés and bakeries that have signed up to the scheme before being reused. 56 coffee retailers have signed up, and 10 000 cups are being used.

One of the main obstacles facing a wider-reaching scheme, however, is the number of café chains in Germany that are unwilling to use unbranded multi-use cups, particularly Starbucks and McDonald’s. Starbucks already offers a discounted coffee for customers with a multi-use cup, but only if it is bearing the unmistakable Starbucks logo.

(c) Examine the advantages of using an indirect tax as a means of reducing the use of disposable coffee cups. (8 points)

Question 10: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2018 Paper 3

Extract D

Indonesia’s economic outlook

The Indonesian economy is expected to grow by an average of 4.8% a year between 2017 and 2021. Joko Widodo, president of Indonesia since 2014, is increasingly confident in his role and now has enough political support to pass some of his desired supply-side reforms. His government has been aggressively trying to improve the business and investment environment by easing regulations and offering tax incentives, for example to firms investing in special economic zones.

Indonesia receives US$2.3 billion a year in overseas development aid, which is mainly spent on education and healthcare. There is also ongoing aid from international institutions and non-government organisations paying for restructuring after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which led to the loss of over 170 000 lives and much damage to economic livelihood. Aid agencies have supported the Indonesian government in providing healthcare free at the point of access for 88 million of the poorest people, free schooling for 12 years for each child, and tertiary education for students accepted into university. There is a scheme to provide each of Indonesia’s 15.5 million poorest households with a cash transfer of 200 000 rupiah (US$14.37) a month. The World Bank has approved US$800 million in infrastructure loans to Indonesia, with another US$950 million as conditional loans. The Asian Development Bank has committed itself to lending US$2 billion. In December Japan’s development agency lent Indonesia US$535 million to construct two power stations.

Extract E

Indonesia’s economic policies as commodity prices collapse

Indonesia is the world’s fourth largest exporter of coal and the raw material accounts for 11% of its exports. Its other main exports are crude oil, palm oil, rubber and tin. Its main commodity exports tripled in value between 2000 and 2010, and as exports boomed, so did the economy. But the value of commodity exports has fallen by more than half from its peak. Coal now sells for just US$50 per tonne, against US$125 in 2011.

In the decade to 2014, Indonesia’s real GDP grew by an annual average of 6%, but the collapse in commodity prices has slowed the economy. In 2015 growth was 4.8%, the slowest rate since 2009. But compared with many other commodity exporters, Indonesia is getting off lightly.

The value of the rupiah, Indonesia’s currency, against the US dollar has fallen by 30% since 2013, but has since stabilised. Other emerging market currencies have depreciated even more steeply over that period. Despite the weak exchange rate, Indonesia’s inflation rate has mostly remained within the central bank’s target range of 3-5%. The main impact of the rupiah’s fall has been to curb imports, helping limit Indonesia’s current account deficit to around 2% of GDP despite weaker export earnings. A cautious fiscal policy during the boom years has allowed for a modest fiscal expansion to offset the effects of weak exports and investment. The national debt is just 26% of GDP.

Mr Widodo knows that Indonesia cannot raise its long-term growth rate if the economy remains reliant on coal. It needs a broader range of manufacturing and service industries. If new enterprise is to flourish, Indonesia must support local entrepreneurship. The labour market is inflexible. To start a business takes an average of 47 days, compared with four in Malaysia and two in Singapore. The President’s supply-side policies are improving the business climate. The average number of days needed to approve a new power plant has declined from 900 to 200. The government recently revised its “negative investment list” of sectors in which foreign ownership is banned or restricted, fully opening up the rubber, film and restaurant sectors, among others. In 2015 he launched a series of measures to try to reduce government failure, including easing some regulations, streamlining licensing procedures for firms on industrial estates and providing tax incentives to invest in special economic zones.

The government has used savings from cutting fuel subsidies, worth over 4% of GDP, to fund extra capital spending. But the budget deficit still widened to 2.8% of GDP, very close to the legal limit of 3%. If public expenditure is to increase further, the government will need to raise more revenue. That will not be easy. Most workers and employers pay little or no tax. Only 27 million of Indonesia’s 255 million people are registered taxpayers, and in 2014 just 900 000 of them paid what they owed, leaving it with a tax revenue to GDP ratio of around 10%. Big companies say that they are being squeezed harder by the tax authorities because they are an easier target.

Infrastructure spending will help bring foreign investment and good jobs to Indonesia as well as encouraging exports. Indonesia’s infrastructure problem can be summed up as too few roads and congested ports. In the short term, infrastructure spending puts people to work and boosts demand for raw materials. In the longer term this spending offers the chance to make up for decades of neglect and underinvestment. Indonesia has plans for 65 dams, 16 of which are already under construction. In 2015 work started on the Keureuto Dam, designed to boost agricultural productivity in Aceh. Recently fields were flooded for the massive Jatigede Dam in West Java, after 20 years of delays. Once complete, the dam will irrigate 90 000 hectares of rice paddy, increasing efficiency by giving farmers two harvests a year instead of one.

(b) Examine the likely effects on the profitability of Indonesian rice farmers of the government’s increased investment in dams (Extract E, lines 43-48). Use a cost and revenue diagram to support your answer. (8 points)

Question 11: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2017 Paper 3

Extract A

Chile’s economic outlook brightens

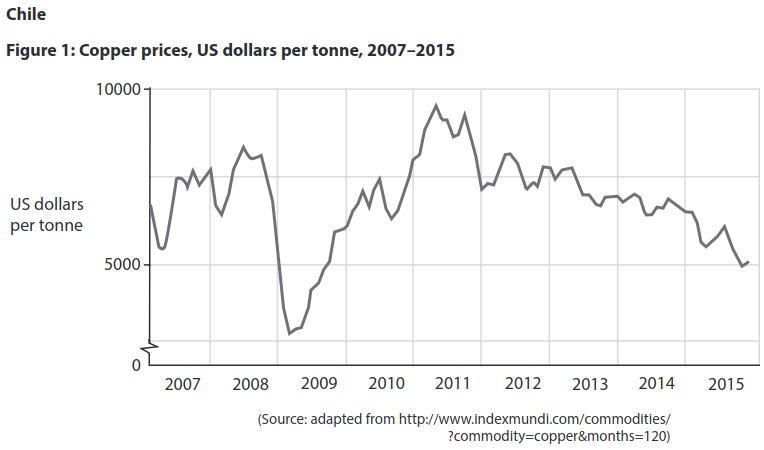

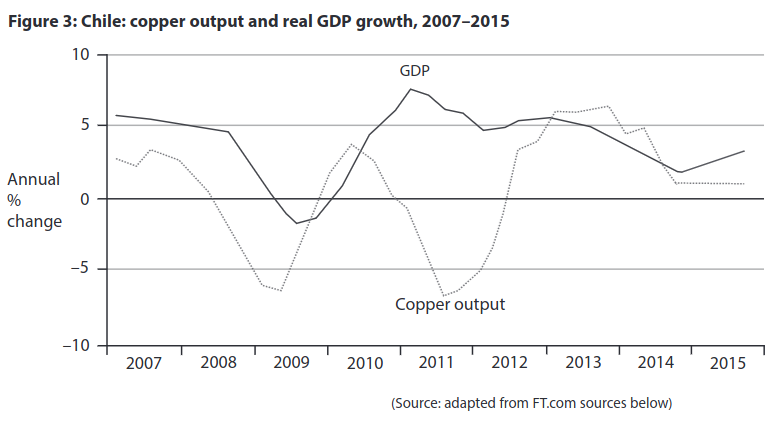

Chile has been hit hard by a worldwide fall in commodity prices since 2011. Copper accounts for 20% of Chile’s GDP and 60% of its exports; one third of the world’s copper is produced by Chile. China purchased 40% of the world’s copper, so a slowdown in China combined with increased global over-supply has meant copper prices have collapsed (see Figure 1). Chilean government income from copper exports had reached $11.5 billion a year before copper prices fell, but now tax revenues from this source have fallen drastically. Growing numbers of copper mines struggle to break even at current prices.

Chile’s GDP is now growing, helped by a weak currency that has boosted export industries outside the mining sector, such as its successful wine and salmon industries. There are strengths in tourism and high-tech products. Public services are good in Chile, and poverty rates have been falling fast. On top of this, a large and diversified financial sector with high domestic savings provides a useful safety net, given high levels of corporate debt and the government’s need to finance a fiscal deficit of 3% of GDP.

Chile’s economy is often regarded as the best run in the region. This is attributed to the credibility of its financial institutions, relatively low levels of national debt (about 15% of GDP) and its free-trade model, which is unrestricted by government interventionism that has distorted the economies of countries such as Argentina and Venezuela. “Chile is an example of how credible institutions can smooth the economic cycle and make adjustments less traumatic,” said Mr Valdés, the minister of finance in Chile, pointing to its widely respected and independent central bank and a well-established fiscal rule that give officials the freedom to implement counter-cyclical policies.

However, there are worries that without enough spare capacity in the economy, expansionary fiscal and monetary policies could end up increasing inflation rather than economic growth. Meanwhile monetary policy is restricted by inflation that has reached 5%, well outside the central bank’s 2–4% target range, fuelled by a weaker exchange rate.

Crucially, investment remains low because of uncertainty over the outcome of the Prime Minister’s reforms, which are aimed at reducing inequality. A recent rise in corporation tax from 20% to 25% and labour market reforms that strengthen the power of trade unions may have a negative effect on business confidence.

Despite a “mildly contractionary” budget, Valdés insisted that the government would continue with costly reforms. Increased taxes on those on higher incomes are considered by the government to be necessary to sustain economic development in Chile. “We do want to change society, while recognising all the good things that have been done in the past 25 years,” said Mr Valdés, referring to an average growth rate of 5.3% over the past three decades, but under 2% in 2015. There is broad consensus that investment in education is the key to unlocking Chile’s growth potential.

Extract B

Chile’s copper mining on a downward track

There was a time when investing in Chilean mining meant guaranteed success. After 1990, when military rule was replaced by an elected government, market reforms and restored relations with the US and UK meant foreign companies were keen to exploit vast copper reserves. The existence of large copper reserves in a stable country with a business-friendly government is rare, making Chile much more attractive to investors than countries such as Zambia.

By mid-2015, however, the copper price hit a six-year low. Chilean mines are becoming less productive. After 20 years of heavy digging, the ore is lower grade, and much further down. The deeper pits take longer to mine, and use more fuel. Wages are high, and trade unions are powerful. A mining truck driver earns $70 000 a year, $10 000 more than the US equivalent. Many mining projects that were planned are being postponed, and investors are looking to Peru; even the US copper mining industry is becoming more competitive.

Energy supply is also a worry as Chile produces virtually no fossil fuels and relies on imported coal and liquid natural gas to power its mines. Energy costs account for 18% of the cost of copper production.

Water supply is also becoming a major problem. Farmers and communities accuse mining companies of causing water shortages to keep their operations running. A prolonged drought has not helped. Mining firms are turning to desalination plants or using untreated seawater. However pumping water 200 kilometres from the Pacific Ocean to the copper mines is costly.

Chile’s environmentalist movement has forced the government to tighten regulations. In 2001, it took 236 days to get an environmental impact assessment of a new mine approved. By 2013, this had increased to 506 days.

(b) Examine the likely impact of externalities of copper mining on firms and communities within Chile. (8 points)

Mark is an A-Level Economics tutor who has been teaching for 6 years. He holds a masters degree with distinction from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh.