We’ve compiled a list of all the government debt questions we could find in Edxecel’s published A-Level Economics past papers. Our goal is to make it easier to revise government debt questions without needing to go through all the papers yourself. Government debt is the money owned when governments borrow funds to pay for government spending. Government debt often takes the form of bonds and may be borrowed from financial institutions, other countries, or individual investors.

What is Edexcel A-Level Economics?

Edexcel A-Level Economics is a pre-university economics course taken by students in their last two years of schooling. The A-Level in economics covers introductory topics that you might expect to cover in a first-year economics course at university.

Edexcel is a private company that is the largest exam board offering A-Level Economics. There are alternatives, namely AQA, CIE, and Eduqas.

How did we pick these A-Level Economics government debt questions?

We picked these Edexcel A-Level Economics government debt questions by going through all the past papers published by Edexcel. Our goal in writing this article was to ensure you could test your understanding of government debt without having to go through all the Edexcel past papers to pick out the questions yourself. The answer key is available at the bottom of this page.

What is government debt?

Government debt is created when governments borrow money in order to pay for public service and government investment. Governments often issue bonds to pay for a fiscal deficit – a gap between the money raised from taxes and the total cost of running government services and other expenses.

The lenders financing government debt might be financial institutions, private individuals, other governments, or any combination of the three. Governments have to pay annual interest on their debt, which is sometimes called “debt servicing.”

The advantage of government debt is that it permits expansionary fiscal spending – significant spending designed to stimulate economic growth. However, this sometimes comes at the cost of high interest rates, which governments will have to pay over time. The cost of paying interest rates cuts into future spending.

Question 1: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 2

After the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the US President introduced expansionary fiscal policies of $800 billion. The International Monetary Fund estimated that the multiplier at the time was approximately 1.5.

(a) Which one of the following is a withdrawal from the circular flow of income? (1 points)

A Exports

B Government spending

C Investment

D Taxation

(b) Calculate the total final increase in US aggregate demand as a result of the President’s ‘expansionary fiscal policies’, assuming no other changes. (2 points)

(c) Explain the impact of annual fiscal deficits on the US national debt. (2 points)

Question 2: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2020 Paper 2

In 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) lent Argentina $57 billion as part of a bailout package to help prevent the country’s government defaulting on its debts. This financial crisis also caused significant capital flight out of Argentina’s economy.

(a) Explain the role of the IMF in providing financial assistance to countries such as Argentina. (4 points)

(b) Which one of the following is most likely to happen to Argentina’s currency value as a result of capital flight, assuming it is operating with a floating exchange rate system? (1 point)

A Appreciation

B Depreciation

C Devaluation

D Revaluation

Question 3: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 May 2019 Paper 2

Japan’s budget deficit for 2017/18 is expected to be 4.6% of GDP. Its national debt is forecast to increase to above 250% of GDP by 2019. Evaluate the impact of a large fiscal deficit and national debt on a country’s economy. (25 points)

Question 4: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 November 2021 Paper 3

Extract C

Why Germany keeps to budget rules despite a slowdown in growth

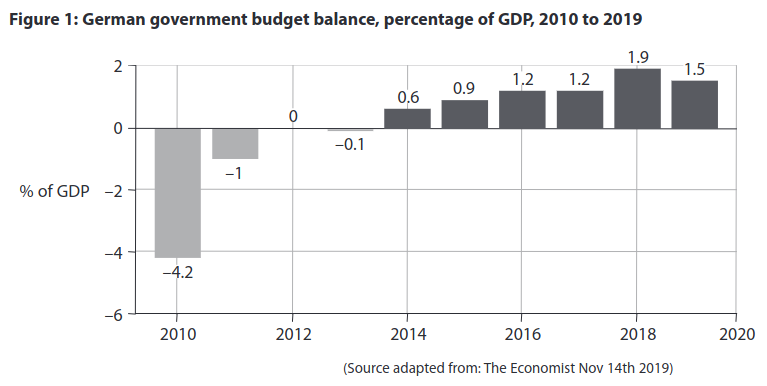

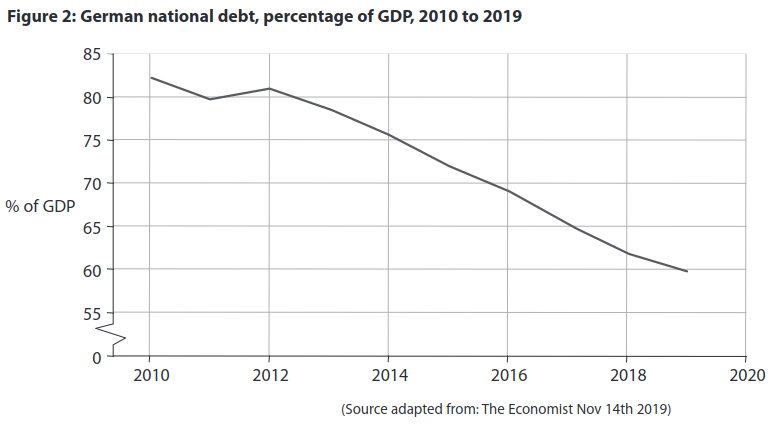

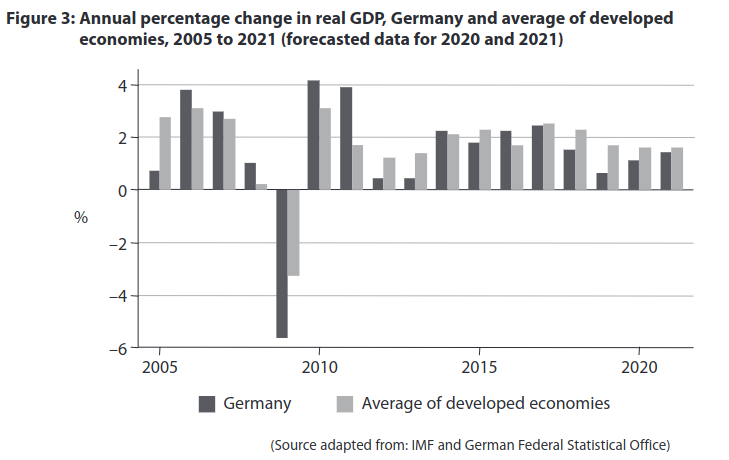

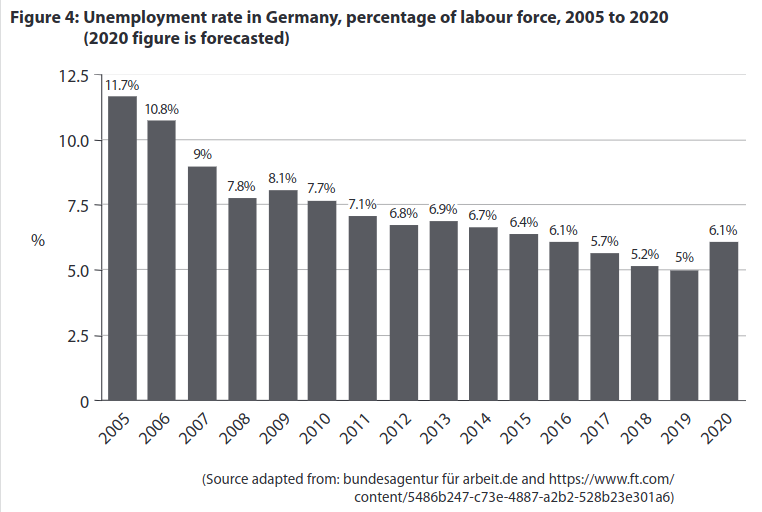

Germany’s economic boom is over, as it has entered recession. During the last ten years of economic growth well over 4 million jobs were created. The fear of recession has revived a debate in Germany: should the government spend more to stimulate growth? It is written into the German constitution that the fiscal deficit cannot be greater than 0.35% of GDP, once the effects of the economic cycle have been removed. Germany’s budget has been in surplus since 2014 and the government is always reluctant to increase spending which would create a deficit. In 2018, aided by booming employment and low interest costs on existing debt, the budget ran to a surplus 1.9% of GDP.

Germany’s main trading partners have long been angered by German fiscal policy. The French President criticised Germany’s budget and current account surpluses that “always occur at the expense of others”.

Large parts of Germany’s infrastructure need significant investment. As the economy has slowed, a decision to run a balanced-budget policy has become harder to defend. In wealthy regions of Germany, crumbling schools have been closed for fear of collapse, and information and mobile technology on a wide scale needs to be modernised. The World Economic Forum reported that accessibility of fibre optic broadband also “remains the privilege of the few”. However, private sector firms, such as major motor manufacturers, are still willing to invest in new technology and the profitability of some of these firms, in the long run, benefits as a result.

The state development bank puts Germany’s investment shortfall at €138 billion (£120 billion). Arguments for a much more expansionary fiscal policy have failed to influence government policy. Big government programmes, such as a recent package to reduce Germany’s carbon emissions, are only implemented when they satisfy fiscal rules.

Extract D

Germany drops to number 7 in the Global Competitiveness Index

Despite being the largest economy in the European Union, Germany’s competitiveness is declining, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). Germany dropped four places in the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index, coming in as the seventh-most competitive economy. Out of the 103 indicators used in the report, Germany received lower scores in 53 areas in 2019.

(a) Explain one reason why a country such as Germany wants to avoid an increase in the national debt relative to GDP (Figure 2). (5 points)

(b) Examine two likely effects of the forecast change in the rate of unemployment between 2019 to 2020, on firms in Germany. Refer to Figure 4 in your answer. (8 points)

(c) Discuss the likely impact of investment in new technology on the profitability of firms in Germany, as described in Extract C line 20. Use a cost and revenue diagram to support your answer. (12 points)

EITHER

(d) Evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic factors which are likely to determine the rate of economic growth in Germany relative to other developed economies. (25 points)

OR

(e) Evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic impacts of ‘a much more expansionary fiscal policy’ (Extract C line 23) on the German economy. (25 points)

Question 5: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2019 Paper 3

Extract D

Rising debt levels in Africa

Increases in national debt have brought several African governments towards a debt-servicing crisis when the repayment of debt and interest become unsustainable. Between 2010 and 2015, many sub-Saharan countries raised debt totalling more than £20 billion. Back then, with commodity prices soaring and foreign loans available at very low interest rates, everyone agreed that borrowing was the way to grow an economy with expansionary fiscal policy. Since 2015, some African governments – beneficiaries of big debt write-offs at the start of the century – have taken to private debt markets too eagerly, leaving them with heavy repayment schedules at a time of lower commodity prices.

Until recently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has played down African debt concerns, pointing to better management of public resources and greater transparency. But it was shaken by Mozambique’s default on more than £2 billion of secret loans used to purchase a non-existent tuna-fishing fleet, raising fears of hidden debt in other African countries with similar levels of corruption. The median level of debt in sub-Saharan Africa had risen sharply from 34% of gross domestic product in 2013 to 48% in 2017. Although that is low by international standards, analysts said debt burdens were heavier than they appeared because of most African countries’ low tax base. “The real thing to look for is debt to revenue, or debt-service as a percentage of government spending,” said John Ashbourne, Africa Economist at Capital Economics. In several countries, he said, debt payments were above 20% of government revenue, with an opportunity cost in terms of

government spending.

Extract E

Mozambique’s economic stability is being put to the test

The economy of Mozambique, which gained independence from Portugal in 1975, has continued to under-perform. Large-scale emigration, especially of skilled workers, economic dependence on South Africa, a severe drought, a prolonged civil war and political tensions have hindered the country’s development. More than half of Mozambique’s 26 million people continue to live below the poverty line.

GDP growth declined to 3.6% in 2016 due to fiscal tightening and a slowdown in foreign direct investment. A weak manufacturing sector employs just 3.2% of the population, and is made up of small enterprises (90%), many of which were set up with the aid of microfinance. Traditional export earnings dropped due to depressed global demand.

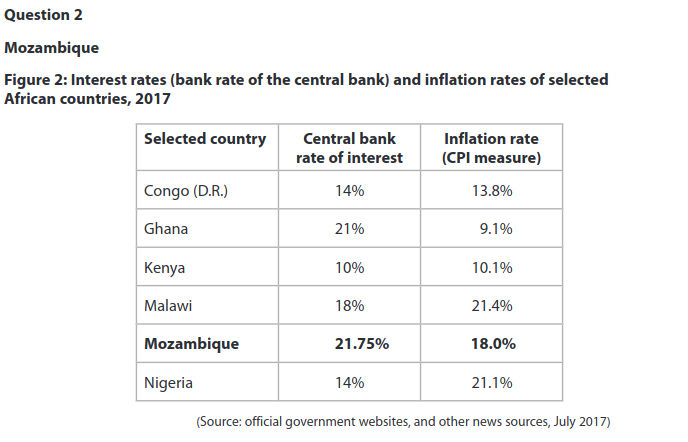

In addition a wide-scale drought seriously affected agricultural production. Foreign currency inflows have weakened – as large-scale gas projects were put on hold, and 14 external lenders suspended direct budget support, as a lesson to be learned from the tuna-fleet scandal. The state budget deficit was 10.7% of GDP in 2017. High interest rates have reduced aggregate demand, and import costs added to inflation following further depreciation of Mozambique’s currency, the metical, to a new low of 100 meticals to £1. Mozambique needs urgently to improve its investment environment and confidence in its institutions. The World Economic Forum’s global competitiveness ranking placed Mozambique 136 out of 137 countries.

Longer term, Mozambique’s economic prospects are promising. There has been progress in talks on restoring international confidence in the government’s running of the economy, leading to a lasting and sustainable agreement between rival political groups. The development of gas fields off Mozambique’s coast discovered in 2011 is set to transform the economy, coming into production in the 2020s. A rise in coal and electricity exports should help growth to increase. But in the short term, it remains uncertain whether Mozambique can deliver badly needed economic stability.

Extract F

Microfinance in Mozambique

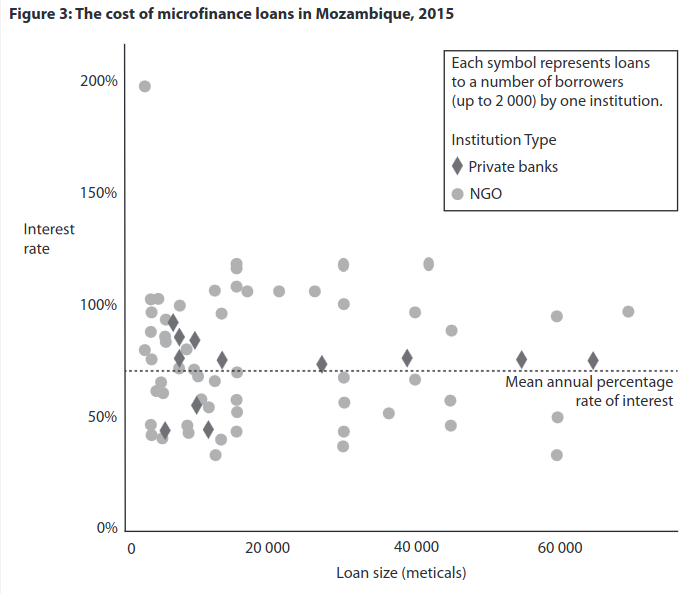

Microfinance in Mozambique started in the late 1980s through projects initiated by international relief organisations. The sector has expanded to include many private banks and non-government organisations (NGOs), see Figure 3. This has resulted in wider use (over 100 000 borrowers) and many new business start-ups which could not have gained finance from any other source. Evidence suggests that there is unfulfilled demand for microfinance and a large potential for expansion.

(a) With reference to Extract D line 21, explain why ‘opportunity cost’ is a problem for governments of developing countries when servicing debt. (5 points)

(b) Examine two reasons, apart from access to finance, why 90% of the manufacturing sector in Mozambique ‘is made up of small enterprises’ (Extract E, line 9). (8 points)

(c) Discuss whether borrowers benefit from microfinance. Make reference to Mozambique in your answer. (12 points)

EITHER

(d) Evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic factors, apart from access to credit and banking, influencing growth and development in Mozambique. (25 points)

OR

(e) Evaluate the likely microeconomic and macroeconomic effects of relatively high inflation rates in many African countries. (25 points)

Question 6: Edexcel A-Level Economics 9EC0 June 2017 Paper 3

Extract C

The National Living Wage (NLW)

The Government has announced that from 2016 it will introduce a Living Wage Premium that will apply on top of the National Minimum Wage (NMW) for employees aged 25 and over to deliver a National Living Wage (NLW) for those people. The main NMW will continue to be set for all employees aged 21 and over, so that those aged 21 to 24 will continue to be subject only to that rate.

The effective minimum wage for the 25+ age group will therefore be over 13% higher in 2020 than would otherwise have been the case, and result in a 0.3% increase in wage costs overall. Further impacts on real GDP are estimated to be higher productivity (+0.3%) but lower average hours worked (-0.2%) and higher unemployment. Overall real GDP is forecast to fall by 0.1% as a result of the NLW. However these forecasts depend on estimates of the likely elasticity of demand for labour.

Academic evidence suggests that changes to the NMW since 1999 have led to only limited effects on demand for labour in the UK. The types of work that will be affected are relatively labour intensive, which may limit the scope for firms to substitute toward using capital. Firms may also be expected to shift demand in favour of the under-25s given that they will not be subject to the NLW, which all else being equal would lead to a smaller reduction in overall labour demand. Some of the reduction in employees could also be partially offset by a rise in self-employment. But increasing the NLW to a higher proportion of median earnings may lead to bigger effects than have been experienced in the past.

Extract D

The productivity puzzle in the UK

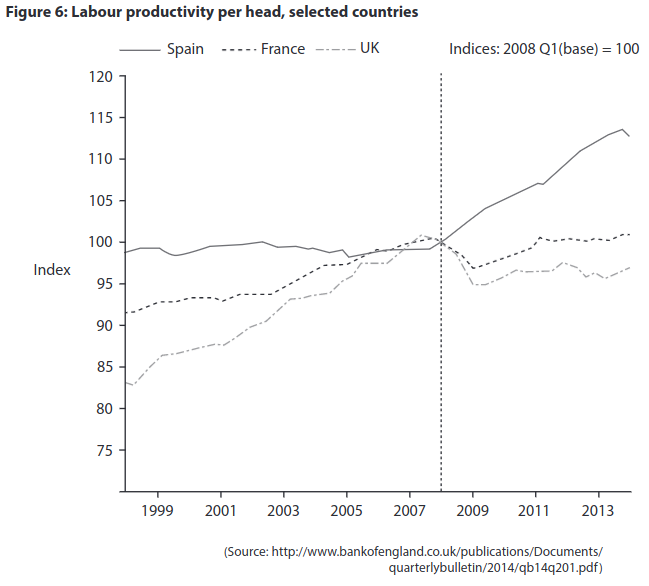

Since the onset of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, labour productivity growth in the UK has been exceptionally weak. Despite some modest improvements in 2013, whole-economy output per hour remains around 16% below the level implied by its pre-crisis trend. Even taking into account possible measurement issues and changes in the size of the service sector, this shortfall is large and is often referred to as the ‘productivity puzzle’.

Measures of productivity can be used to inform estimates of an economy’s ability to grow without generating excessive inflationary pressure, which makes understanding recent movements important for the conduct of monetary policy. During the initial phases of the recession, companies appear to have acted flexibly by holding on to labour and lowering levels of capacity utilisation in response to weak demand conditions. But the protracted weakness in productivity and the strength in employment growth over the past two years suggest that other factors are likely to be having a more persistent impact on the level of productivity. These factors are reduced investment in both physical and intangible capital, such as innovation and training, and failings in the labour market such as immobility of labour and under-employment of skilled workers. Some economists explain this by using the concept of an output gap.

(a) With reference to Extract D (line 18), explain the meaning of the term ‘output gap’. Use an aggregate demand and aggregate supply diagram in your answer. (5 points)

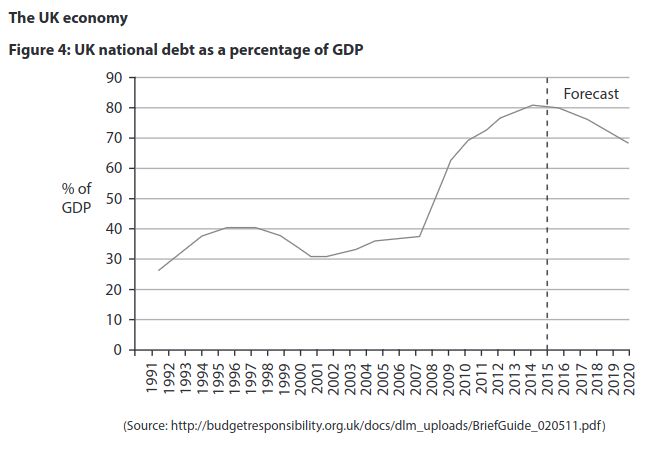

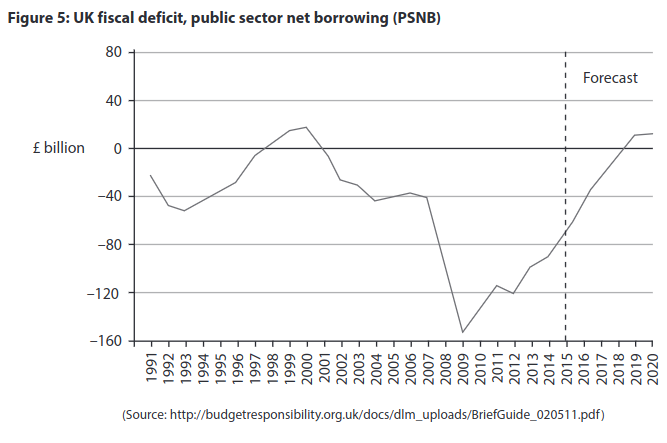

(b) With reference to Figures 4 and 5 and your own knowledge, examine the relationship between the national debt as a proportion of GDP and the fiscal deficit. (8 points)

(c) Discuss the likely impact of the National Living Wage on the profitability of firms. Use a cost and revenue diagram in your answer. (12 points)

EITHER

(d) With reference to the information provided and your own knowledge, evaluate the likely microeconomic and macroeconomic influences on the UK’s international competitiveness. (25 points)

OR

(e) With reference to the information provided and your own knowledge, evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic effects of a government policy of cutting public expenditure rather than raising taxes as a means of reducing a fiscal deficit. (25 points)

Mark is an A-Level Economics tutor who has been teaching for 6 years. He holds a masters degree with distinction from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh.