What is the Edexcel A-Level Economics test?

The Edexcel A-Level Economics test is an economics-focused qualification offered to British students in their final two years of secondary school study. A-levels are typically taken as courses intended to lead to University or other further education. A-level economics students will often go on to study economics or a similar subject at University.

The Edexcel A-Level Economics test is offered by Pearson Edexcel. The main alternative to Edexcel is the AQA A-Level Economics course.

Edexcel is a privately-owned British education and exams body founded in 1996. Edexcel has been owned by Pearson plc. since 2005. Edexcel produces qualifications and tests for the British education system and is the UK’s largest entity offering educational qualifications.

Where did we get these Edexcel Economics A-Level Past Paper Indirect Taxes and Government Subsidies Questions?

We found these Edexcel Economics A-Level Past Paper indirect taxes and government subsidies questions by going through past Edexcel A-Level Economics papers according to the current specification. We picked out indirect taxes and government subsidies questions and put them together in this list so that you can go through them without having to search through the different Edexcel A-Level Economics papers currently online.

Want questions for other topics in A-Level Economics? You can find more A-Level Economics Past Paper Questions here.

What is an indirect tax?

An indirect tax is a tax applied to the sale of a good or service rather than to the income or revenue of a person or business. Examples of indirect taxes include VAT, an alcohol tax, or a tax on petrol. Indirect taxes can be paid at the point of sale – as with a sales tax – or at the point of production – as with emissions taxes. However, companies charged indirect taxes during the manufacture of a product are likely to put up prices, thus passing the cost of the tax on to the consumer.

An indirect tax is the opposite of a direct tax, which is applied to the revenue of a business or the income of a person. A corporate tax or personal income tax are both examples of direct taxes.

Governments often apply indirect taxes as a way to discourage the consumption of certain kinds of goods or services, such as cigarettes or alcohol, that have negative social consequences. This kind of indirect tax is commonly called a “vice tax.”

Indirect taxes are often criticised as falling disproportionately on individuals with lower incomes. Everyone pays the same amount for an indirect tax but these taxes will form a higher percentage of the income of someone who earns less. This is especially relevant when compared against income taxes, which often increase as a person’s income increases.

What is a government subsidy?

A government subsidy is a benefit given by the government to a business or individual, often for engaging in behaviour the government wishes to encourage. Government subsidies may be used to make doing business in a particular sector more appealing or to ease the burden of costs on individuals or families.

An example of a government subsidy would be a petrol subsidy, in which the government contributes a certain amount to every purchase of petrol so that its price for the consumer is lower. The intention of this subsidy is to make access to petrol – and thus transport – more accessible to those with lower incomes. Lower petrol prices may also contribute to economic growth by making the production and transport of certain goods more affordable.

Another example of a government subsidy would be a tax break on corporate taxes for business that hit low emissions targets. Rather than giving money to the business in this instance, the government is refraining from collecting corporate taxes as a way to encourage reduced emissions. The effect of a tax cut of this kind may be to reduce prices for greener goods as companies may pass on these savings to consumers by lowering prices.

You can check out our Edexcel A-Level Economics Notes here.

Question 1: Edexcel 9ECO November 2021 Paper 1

Patrick Street Productions produces musicals. Its latest production is ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ and the total cost of this production is $200 000. The ticket price is $40. The theatre has a capacity of 300 seats. The company aims for revenue maximisation. If this is achieved, revenue from ticket sales will cover 30% of total costs. Charitable donations contribute 12.5% towards total cost and a government subsidy ensures the production covers all of its costs.

(a) Calculate the total revenue from ticket sales for ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’, assuming it is shown only five times, all at full capacity. You are advised to show your working. (2 points)

(b) Calculate the value of the government subsidy necessary for this production to cover all of its costs. (2 points)

(c) Which one of the following conditions is necessary for revenue maximisation to occur? (1 point)

A Average revenue equals average cost

B Average revenue equals marginal cost

C Marginal revenue equals average revenue

D Marginal revenue equals zero

Question 2: Edexcel 9ECO November 2021 Paper 1

Extract A

Marginal productivity of cabin crew

Cabin crew are responsible for loading passengers and providing in-flight meals. United Airlines is planning to reduce the number of its cabin crew members onboard international flights. The airline currently operates its planes with one more cabin crew member than its competitors. The marginal productivity of this additional crew member may be low. By reducing the number of its cabin crew members United Airlines will be able to operate more efficiently and compete more effectively.

Extract B

Thomas Cook’s environmental impact

Thomas Cook Group plc’s operations included its airline and 560 high street travel agents providing flights, hotels and package holidays.

The environmental impact of the travel industry is significant. It accounts for 8% of all global carbon emissions. Thomas Cook recognised the risks presented by climate change and actively engaged in reducing their airline emissions. Its plans included using more efficient aircraft and using lower-carbon fuel. In 2018, Thomas Cook was included in the top 10 of the world’s most fuel-efficient airlines.

Extract C

Why did Thomas Cook shut down?

Thomas Cook Group plc ceased trading on 23 September 2019. The collapse of Thomas Cook left 600 000 travellers stranded overseas and approximately 21 000 worldwide employees were left without a job.

Thomas Cook’s management said that the failure of rescue talks between banks, shareholders and the UK Government meant it had no choice but to shut down the business. But in truth the tour operator’s problems go back much further. A disastrous merger in 2007, increased debts, the internet revolution in holiday booking and Brexit uncertainty all contributed to the failure of the business.

In 2007 it merged with MyTravel. Thomas Cook directors had an objective of rapid company growth over short-term profitability. The merger was supposed to create a European giant, promising £75 million-a-year cost savings and a springboard to challenge emerging internet rivals. In reality, Thomas Cook was merging with a company that had only made a profit once in the previous six years, and the deal left the Group with huge debts. In May 2019, the firm reported a £1.5 billion loss.

The role of the management in Thomas Cook’s collapse is being investigated by the UK Government. Thomas Cook executives’ salaries and bonuses have been questioned. Directors received salaries totalling £20 million in the five years before its collapse. The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) earned a £500 000 cash bonus in 2017 and about £8.5 million in his five years with the company. It seems that around £4 million of this was in the form of shares. The share price reached £1.46 in 2018, but each share is now worthless.

The CEO said that the directors had worked “exhaustively” to rescue Thomas Cook and create a long-term turnaround strategy. “It is a matter of profound regret to me and the rest of the board that we were not successful.”

The UK prime minister admitted that the government refused to grant £150 million as a subsidy to help rescue Thomas Cook in the short run. The UK prime minister stated: “Clearly, that is a lot of taxpayers’ money and sets up, as people will appreciate, a moral hazard in the case of future such commercial difficulties that companies face. I have questions about whether it’s right that the directors, or whoever, the board, should pay themselves large sums when businesses can go down the tubes like that. One is driven to reflect on whether the directors of these companies are properly incentivised to sort such matters out”.

(a) Explain the likely impact of diminishing marginal productivity of labour on cabin crew staffing levels. Refer to Extract A in your answer. (5 points)

(b) Examine the likely impact of Thomas Cook’s plan ‘to reduce their airline emissions’ (Extract B, line 6) on the social optimum position. Use an appropriate externalities diagram in your answer. (8 points)

(c) With reference to Extract C, assess whether Thomas Cook’s failure was caused by the principal-agent problem. (10 points)

(d) With reference to Extract C, discuss the proposed government subsidy to prevent Thomas Cook from reaching its shut-down point. (12 points)

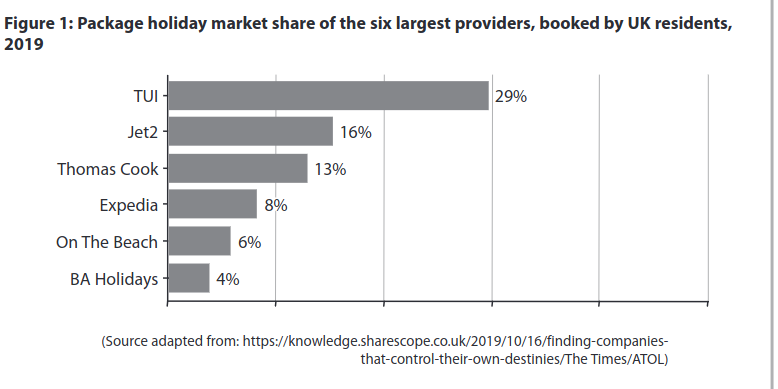

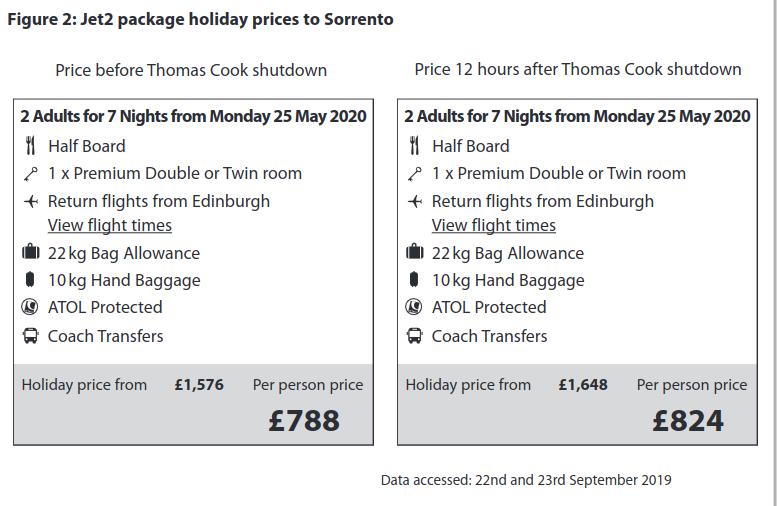

(e) With reference to the information provided, discuss the decision by Jet2 to increase its package holiday prices. (15 points)

Question 3: Edexcel 9ECO November 2020 Paper 1

Fuel duty is an excise tax imposed on the sale of petrol, included in the price paid by consumers, set at 58 pence per litre.

(a) Draw a supply and demand diagram to show the incidence of a specific petrol tax on consumers and producers. (4 points)

(b) The indirect tax on fuel is increased in a market in which the price elasticity of demand is −0.1. Which one of the following is the most likely effect on consumer and producer surplus? (1 points)

A Consumer surplus and producer surplus both decrease

B Consumer surplus and producer surplus both increase

C Consumer surplus decreases and producer surplus increases

D Consumer surplus increases and producer surplus decreases

Question 4: Edexcel 9ECO November 2020 Paper 1

Extract A

The case for nationalisation

Privatisation has not made the rail industry cheaper to operate, despite the promise from one government source that it would see private companies bringing: “more competition, greater efficiency and a wider choice of services”.

One reason, suggest the critics, is fragmentation. Instead of pushing British Rail into the private sector as a single supplier the government chose to break it into three components of track, train operators and rolling stock i.e. the trains and carriages. This has encouraged each part of the rail industry to prioritise its own profits rather than collaborating to improve the system.

Privatisation, meanwhile, never really worked. The rail network of 2 500 stations and 32 000 km of tracks was renationalised in 2001. This has encouraged the government’s transport secretary, a supporter of private sector involvement, to argue that the state Network Rail monopoly should be removed so that companies can bid to build new rail lines to upgrade the railway.

The privately-owned train operators are now the subject of fierce criticism, due to overcrowding and cancelled services. Private companies are supposed to compete to win a bid to be the train operator for a region for a short number of years. However in recent years the number of private companies bidding or renewing their contract as rail operators has fallen. In May 2018 the government rescued the East Coast line by renationalising it. The line had been run by the private rail operator Virgin Rail, which was suffering lower passenger numbers and revenue than forecast.

Some argue that there is a simple solution: reunite track and train in the only feasible manner, nationalisation.

Extract B

Southern Rail boss paid £495 000

The Chief Executive of Southern Rail, the private-sector train operator that has become associated with delays, losses, cancellations and strikes, was paid £495 000 last year. This increased calls for nationalisation and a maximum wage for executives at companies with government contracts. In contrast the average base pay for a train driver in the UK is £47 705, although they can earn up to £63 000.

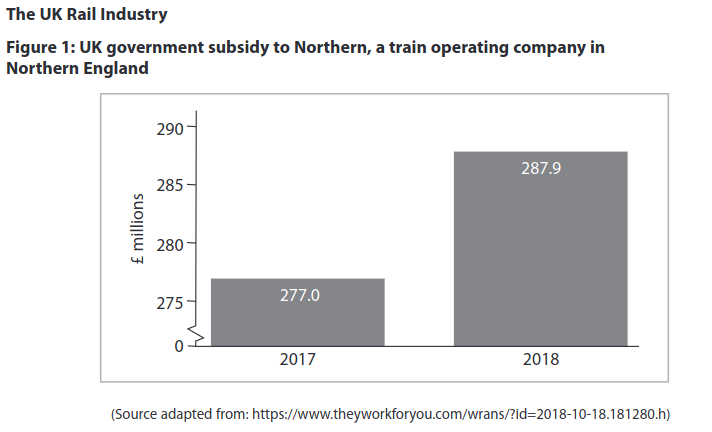

(a) Refer to Figure 1. Explain the likely effect of the change in subsidy levels between 2017 and 2018 on rail fares. Include a supply and demand diagram in your answer. (5 points)

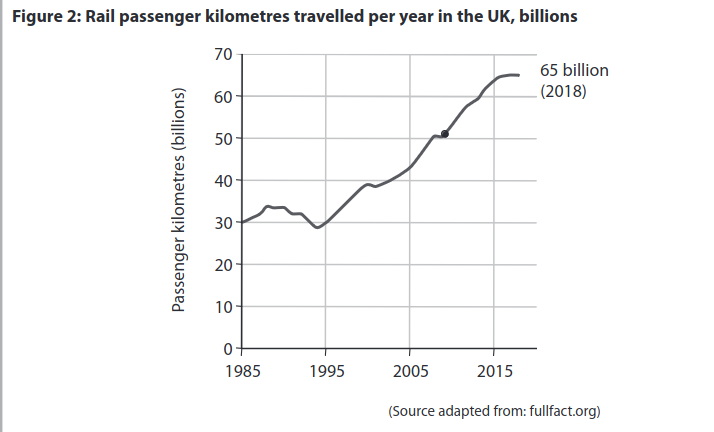

(b) With reference to Figure 2, examine two possible factors which may have influenced demand for rail travel since 2008. (8 points)

(c) Assess whether complete nationalisation of the rail industry might protect employees. (10 points)

(d) With reference to Extract A, paragraph 3, discuss whether the rail network can be considered to be a natural monopoly. (12 points)

(e) Discuss the likely benefits of price discrimination to rail passengers. Use a diagram to support your answer. (15 points)

Question 5: Edexcel 9ECO June 2017 Paper 1

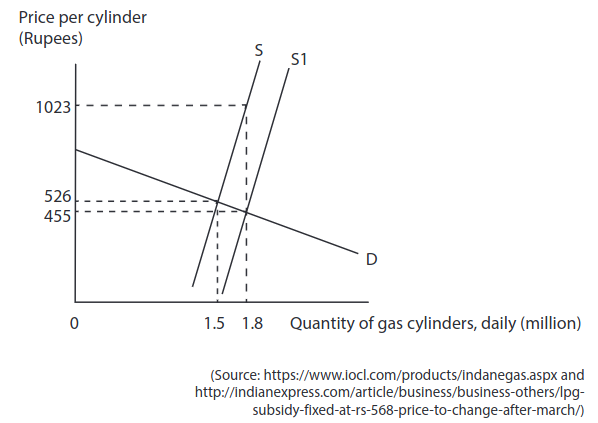

The Indian government has introduced a subsidy on domestic cooking gas cylinders in the city of Mumbai. The diagram below shows the effect following the introduction of the subsidy.

(a) Calculate the total domestic cooking gas subsidy paid daily by the Indian government. You are advised to show your working. (2 points)

(b) Calculate the percentage share of the total subsidy received by:

(i) consumers (1 point)

(ii) producers (1 points)

(c) One effect of the subsidy is to increase: (1 point)

A consumer surplus

B market failure

C public good provision

D tax revenue

Question 6: Edexcel 9ECO June 2017 Paper 1

In 2015 a report by Public Health England recommended the imposition of a 20% tax on the sale of soft drinks that contain high levels of sugar. Evaluate the likely microeconomic effects of such a tax. (25 points)

Question 7: Edexcel 9ECO June 2019 Paper 3

Extract A

The effects of a total ban on advertising of HFSS foods

Food and drinks which are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) tend to be sold in highly concentrated markets. Tough new rules banning advertisements for HFSS products, such as those for confectionery, fizzy drinks and potato crisps, come into effect in July 2017 as means to reduce consumption. The rules apply to media targeted at under-16s and will mean a major reduction in the number of advertisements children see for HFSS products in posters near schools, in films targeted at children, on catch-up television and in social media if it is directed at children.

There are three main factors that will determine the effectiveness of the intervention: first, whether advertising acts to expand the market share or steal rivals’ market share. Secondly, how firms in the market adapt their behaviour in response to the ban. Thirdly, what substitute products do consumers turn to if they opted out of the targeted market.

Results from a recent survey in the UK suggest that the total quantity of crisps sold would fall by around 15% in the presence of an advertising ban, or by 10% if firms respond with price cuts, since the ban acts to make the market more competitive and firms respond to the ban by, on average, lowering their prices.

The survey showed that following a ban, consumers are more likely to switch to another junk food than to a healthy food, which (in addition to the pricing response of firms) acts to partially offset any health gains from the policy.

Extract B

Taxing HFSS foods and subsidising healthy eating widens inequality

Since low-income groups spend a higher proportion of their income on food and tend to eat less healthily, they are the main targets of taxes on products that are high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS). Subsidies on healthy food are seen as an alternative policy approach to encourage healthy eating. While data on the impact of such policies are scarce, a recent study on the distributional impacts of HFSS taxes and healthy food subsidies found that these actually widened health and fiscal inequalities. The policies tend to be regressive and favour higher-income consumers. Taxes on unhealthy food increase prices which have a greater impact on low income groups rather than higher income groups. Lower income groups prefer to buy HFSS food.

Subsidies encouraged all income groups to buy more fruit and vegetables. However, those on higher incomes proved more responsive and the average share of budget spent on healthy food actually increased for the higher income groups who were more likely to buy the subsidised healthy food and then spend the savings they had enjoyed on yet more healthy food. The diets of the higher income groups before the subsidy tended to be healthier. The choices of the higher income groups are more responsive to price changes. By contrast, lower income groups, if they responded to lower prices, often used the money saved to buy unhealthy items or something else entirely. The long-term benefits of a healthier diet are harder to grasp for consumers when information gaps exist. Often the immediate boost of a tasty treat is more appealing. Taxes and subsidies do not change that. Other strategies are needed to promote healthy eating, especially education.

Extract C

Tax on fatty foods in Denmark is an economic disaster

Denmark introduced a specific tax on saturated fat in October 2011. Recognised as a world-leading public health policy, it was abandoned just 15 months later having been both an economic and political disaster.

Indirect taxes of this sort are invariably regressive, disproportionately affecting the elderly and the poor. The specific tax led to prices rising on average 15% for highest-fat products, yielding a total decrease of 5% in the intake of saturated fat from products such as minced beef and cream. 80% of Danish consumers did not change their shopping habits at all. The behavioural change was economically damaging as consumers switched to cheaper brands and crossed the border to Sweden and Germany to do their shopping. Danish tax revenue fell as a result.

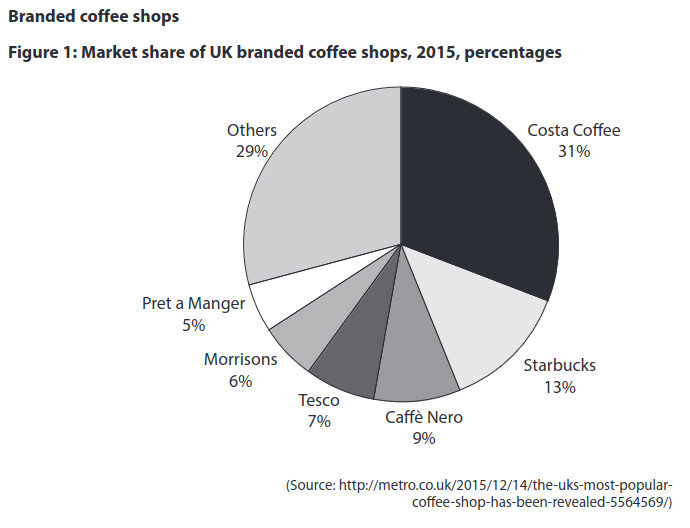

(a) With reference to Figure 1 and Extract A, explain what is meant by a ‘highly concentrated’ market for potato crisps (Extract A, lines 2–3). (5 points)

(b) Apart from changes in indirect taxes and subsidies, examine two causes of income inequality within a developed economy such as the UK. (8 points)

(c) In Extract A, lines 15–16, it was suggested that some firms may respond to the advertising ban by cutting the prices of their products.

Using game theory and the information provided in Figure 1 and Extract A, discuss the effects on firms of cutting prices in an oligopolistic market. (12 points)

EITHER

(d) Evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic effects of increased government spending on education to promote healthy eating in the UK. (25 points)

OR

(e) Evaluate the likely microeconomic and macroeconomic effects of imposing a tax

on HFSS foods. (25 points)

Question 8: Edexcel 9ECO June 2018 Paper 3

Extract A

Starbucks in Britain – a loss-making business?

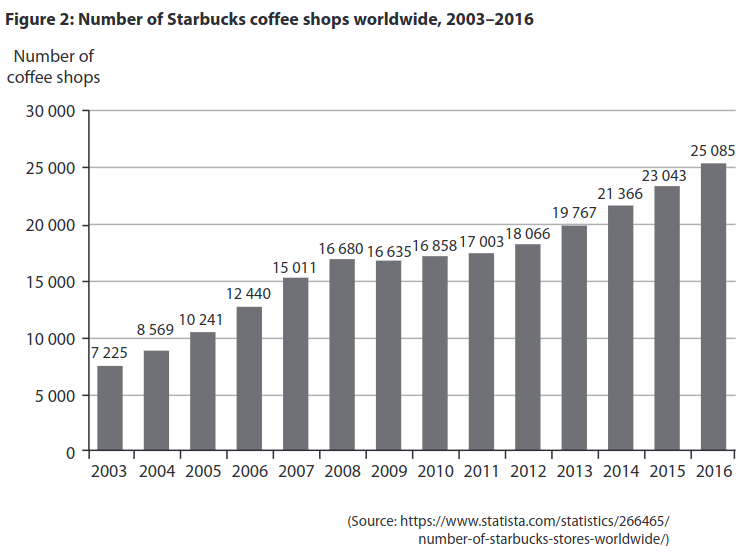

Coffee shops are among the most profitable parts of the food and drink industry, and few are doing quite as well as Starbucks, a US-based transnational company. Starbucks may be complaining of adverse global market conditions but that did not stop the world’s biggest coffee chain from reporting record annual profits in 2016. It made a profit of almost US$4.2 billion for the year, up 16% on 2015. That was mainly the result of a strong performance in its biggest market, America, where revenue rose 11%. The fastest growth was in the China and Asia Pacific region, with revenue up 23%. Howard Schultz, the CEO of Starbucks, said its Chinese coffee shops were the most efficient and profitable. While Starbucks still makes most of its profit in the US, Mr Schultz has said expansion in China will secure its future for “decades to come” and announced plans to more than double the number of shops in China to 5 000 by 2021.

However its British subsidiary, at first glance, appears to be doing less well. It has announced its first ever profit in Britain in 2015 – of just £1 million – despite opening its first coffee shop in the UK in 1998. It now has 849 UK outlets. The main reason why Starbucks has reported persistent losses in the UK is not due to a lack of demand for its coffee, but to minimise its tax bill. It is claimed that some of Starbucks’ revenue earned in the UK is transferred to its Dutch subsidiary, which is charged lower rates of tax.

Starbucks is not finding life as easy in Britain as in the USA. It faces competition from home-grown chains such as Costa and Caffè Nero. Accusations of tax avoidance have also damaged Starbucks’ sales to the benefit of its competitors. A survey found that a third less people rated Starbucks as their preferred coffee shop than they did before the tax- avoidance allegations were first published.

These issues have forced Starbucks to change its strategy. It has slowed down its expansion plans in the UK and has closed 67 underperforming coffee shops over the past year. It has also tried to repair its reputation by transferring its European headquarters from Amsterdam to London.

Extract B

Tax on disposable coffee cups?

Two and a half billion disposable cups are thrown away every year in the UK, that is, seven million every day. Only one in 400 is recycled. The UK Environment Minister has suggested that a coffee cup tax could work in a similar manner to the plastic bag charge. The 5 pence a bag charge has led to an 85% reduction in the number of bags being given out since October 2015. It is estimated that introducing a tax on disposable coffee cups would cut usage by two billion every year. One environment spokesperson, Kate Parminter, said: “We’ve seen how dramatically a small charge has affected public behaviour when it comes to the plastic bags and it is clearly time to extend it to coffee cups. Most people purchase a tea or coffee and throw away the cup without even thinking about it, but a charge would increase our awareness of the environmental impact.”

In response, another MP welcomed her comments but said he did not believe a tax was the solution. He said: “My initial reaction is charging 5p or 10p for the cup will not work. It will not encourage people to take their own cups in if a coffee goes up from £2.60 to £2.65. I suspect a more technological answer is what we need – either the composition of the disposable cups being changed so they’re more easily recyclable, or changing the technology in the recycling.”

Disposable coffee cups contain a plastic coating inside the cups which prevent them from becoming soggy, making them difficult to recycle. There are just two specialist facilities in the UK that have the required equipment to separate plastic from paper for recycling. Almost no recycled paper is used in the production of disposable cups, meaning that some 43 000 trees must be cut down annually to keep up with the demand. CO emissions of around 83 000 tonnes are generated every year for their production.

Extract C

German city of Freiburg takes action on cutting the use of disposable coffee cups

The ‘Freiburg cup’, made from dishwasher-proof plastic, can be reused hundreds of times. Cups are issued with a one-euro deposit, and can be returned to any of the participating coffee shops in the German city. The cups, which are provided to coffee shops by local councils, are washed in the cafés and bakeries that have signed up to the scheme before being reused. 56 coffee retailers have signed up, and 10 000 cups are being used.

One of the main obstacles facing a wider-reaching scheme, however, is the number of café chains in Germany that are unwilling to use unbranded multi-use cups, particularly Starbucks and McDonald’s. Starbucks already offers a discounted coffee for customers with a multi-use cup, but only if it is bearing the unmistakable Starbucks logo.

(a) With reference to Figure 1, briefly explain the market structure that best describes the UK branded coffee shop market. (5 points)

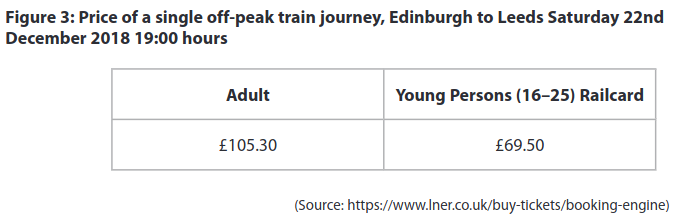

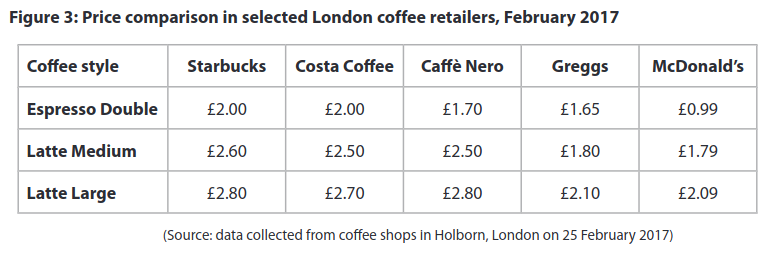

(b) With reference to Figure 3 and other information provided, discuss the price and non-price strategies that Starbucks may use to increase profitability. (12 points)

(c) Examine the advantages of using an indirect tax as a means of reducing the use of disposable coffee cups. (8 points)

EITHER

(d) Evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic factors that may influence Starbucks’ decision whether to expand in a particular country. (25 points)

OR

(e) With reference to the information provided and your own knowledge, evaluate the microeconomic and macroeconomic effects of increased UK demand for coffee at branded coffee shops. (25 points)

Mark is an A-Level Economics tutor who has been teaching for 6 years. He holds a masters degree with distinction from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh.