Definitions

- Inflation: A general increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy, leading to a decrease in the purchasing power of money[3][4].

- Deflation: A decline in the general price level, indicated by an annual inflation rate below 0%[2].

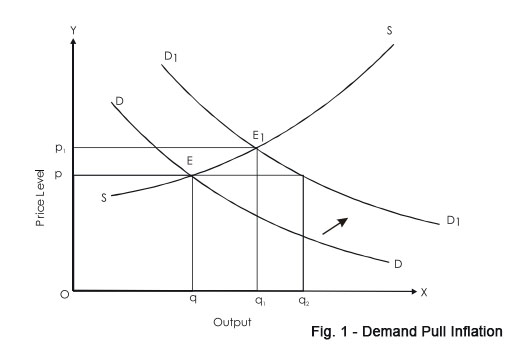

- Demand-Pull Inflation: Inflation caused by an increase in demand for goods and services, often due to increased consumer spending or government expenditure[6].

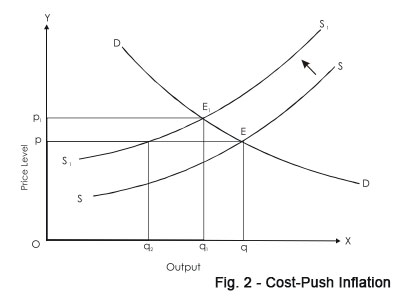

- Cost-Push Inflation: Inflation resulting from a decrease in aggregate supply due to higher costs of production, such as increased wages or raw material prices[6].

- Stagflation: A situation where economic growth is slow but inflation is high, usually accompanied by high unemployment and low wage growth[5].

- Purchasing Power: The ability of money to buy goods and services. Inflation erodes purchasing power[3].

- Consumer Price Index (CPI): A measure used to evaluate the average change over time in the prices paid by consumers for goods and services.

- Producer Price Index (PPI): A measure of the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers for their output.

- Monetary Policy: Government or central bank policies aimed at regulating the level of money supply and interest rates to control inflation.

- Fiscal Policy: Government policies related to taxation and spending to control inflation.

Want notes on other topics? You can check out our Edexcel A-Level Economics Notes here.

Diagrams

Figure 1: Demand-pull inflation

Figure 2: Cost-push Inflation

How Inflation is Measured

Inflation is the decrease in the purchasing power of money, which results in a general increase in the prices of goods and services[1]. It’s a measure of the rate at which these prices rise[2].

Inflation is commonly measured using two main indicators: the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Producer Price Index (PPI).

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- What It Measures: CPI evaluates the average change in prices of a fixed basket of goods and services that households typically buy. It reflects inflation as experienced by consumers in their day-to-day living expenses[1][6].

- Limitations: Despite its widespread use, CPI has limitations like not accounting for quality improvements in products or changes in consumer preferences[3].

- Real-world Example: If a basket of goods cost $100 last year and costs $110 this year, the CPI-based inflation rate would be 10%.

Producer Price Index (PPI)

- What It Measures: PPI tracks the average change in selling prices received by domestic producers for their output. It measures inflation before it reaches the consumer[1].

- Real-world Example: If a factory sold a widget for $50 last year and sells it for $55 this year, the PPI-based inflation rate would be 10%.

CPI vs PPI

CPI focuses on the retail prices of goods and services, while PPI looks at the wholesale level. Both are crucial for understanding different aspects of inflation but can sometimes diverge due to factors like production costs[5].

Want to test your knowledge? You can find A-Level Economics Past Paper Questions here.

Causes of Inflation

- Global Causes:

- Commodity Prices: A rise in global oil prices can lead to cost-push inflation. Higher oil prices increase the cost of goods and services worldwide[5].

- National Causes:

- Economic Expansion: A growing economy can lead to demand-pull inflation as more people have money to spend but the supply of goods remains the same[2].

- Policy Causes:

- Government Spending: Increased government expenditure can also cause demand-pull inflation. More money in the economy boosts demand but not necessarily supply[2].

Types of Inflation

- Demand-Pull Inflation:

- What it is: Occurs when the total demand for goods and services exceeds supply[1].

- Real-World Example: Black Friday sales can lead to demand-pull inflation. High demand for discounted items can exceed supply, causing prices to rise.

- Cost-Push Inflation:

- What it is: Happens when the supply of goods and services falls, often due to increased production costs[4].

- Real-World Example: A hurricane damaging crops can lead to cost-push inflation. The reduced supply of crops increases the cost of food items.

Difference Between Demand-Pull and Cost-Push

- Demand-Pull: Driven by an increase in demand.

- Cost-Push: Driven by a decrease in supply.

- Overlap: Cost-push inflation can kick in when demand-pull inflation is strong. For example, if high demand for a product leads to increased raw material costs, both types of inflation can occur simultaneously[6].

Consequences of Inflation

Consequences for the Economy

- Lost Purchasing Power: Inflation erodes the value of money. For example, if a loaf of bread costs $1 today and inflation is 10%, it will cost $1.10 next year. This affects both consumers and businesses[2].

- Economic Distortions: High inflation can create imbalances in the economy, such as making exports more expensive and less competitive[3].

- Increased Production: On the flip side, moderate inflation can stimulate economic activity. Businesses may produce more, leading to more jobs[6].

Consequences for Individuals

- Reduced Purchasing Power: As prices rise, the same amount of money buys less. This is especially hard on fixed-income groups like retirees[2].

- Income Redistribution: Inflation can have a regressive effect, hitting lower-income families harder. For example, if gas prices rise, it takes a bigger chunk out of a smaller paycheck[5].

- Change in Spending: People might cut back on non-essential items or switch to cheaper alternatives. For instance, instead of dining out, families might opt for home-cooked meals[4].

Policies to Counter Inflation

Monetary Policy Solutions

- Raising Interest Rates: Central banks, like the Federal Reserve in the U.S., can increase interest rates to make borrowing more expensive. This reduces spending and slows down inflation. For example, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates multiple times in 2018 to combat rising inflation.

- Reducing Money Supply: The central bank can also sell government bonds to reduce the amount of money in circulation. Less money means less spending, which can help control inflation.

Fiscal Policy Solutions

- Reducing Government Spending: By cutting back on projects or social programs, the government can reduce the amount of money in the economy, thus curbing demand-pull inflation. For instance, austerity measures were used in Greece to combat high inflation.

- Increasing Taxes: Higher taxes leave people with less disposable income to spend, reducing demand and thereby inflation. This was the approach taken by the U.K. government in the early 1980s.

- Price Controls: Though less common, the government can directly intervene to set price ceilings on essential goods. However, this can lead to problems like shortages. For example, Venezuela tried to control prices on food items, which led to widespread shortages.

Combined Approaches

- Using Both Monetary and Fiscal Policies: Sometimes, a mix of both policies is the most effective. For example, during the stagflation of the 1970s in the U.S., a combination of monetary tightening and fiscal restraint was used.

- Forward Guidance: Central banks can also influence expectations about future inflation and interest rates, thereby affecting current economic behavior. The European Central Bank often uses this tool to manage inflation expectations.

Mark is an A-Level Economics tutor who has been teaching for 6 years. He holds a masters degree with distinction from the London School of Economics and an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh.